Forked Repositories

(2025-07-22T20:58.332Z)

Perplexity Query

(2025-07-22T20:58

.332Z)

Question:

Write a comprehensive one-page article about "Forked/Forking Repositories on GitHub".

Structure the article as follows:

- Introduction (2-3 sentences)

- Define the term and its significance

- Provide context for why it matters

- Main Content (3-4 paragraphs)

- Explain the concept in detail

- Include practical examples and use cases

- Discuss benefits and potential applications

- Address any challenges or considerations

- Current State and Trends (1-2 paragraphs)

- Discuss current adoption and market status

- Mention key players or technologies

- Highlight recent developments

- Future Outlook (1 paragraph)

- Predict future developments

- Discuss potential impact

- Conclusion (1-2 sentences)

- Summarize key points

- End with a forward-looking statement

Important Guidelines:

- Keep the total length to approximately one page (500-800 words)

- Use clear, accessible language

- Include specific examples and real-world applications

- Make it engaging and informative for a general audience

- Use markdown formatting for structure

Image References:

Include

Forked/Forking Repositories on GitHub: Empowering Open Collaboration

Forked repositories on GitHub are independent copies of an existing codebase, enabling users to make changes in their own space without impacting the original project. This concept is central to open source development, providing a framework for collaboration, experimentation, and innovation without compromising the integrity of the main repository[^1jsxhq][^1qb0if].

Understanding Forked Repositories

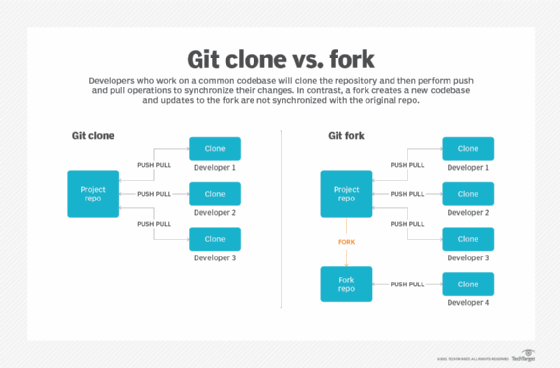

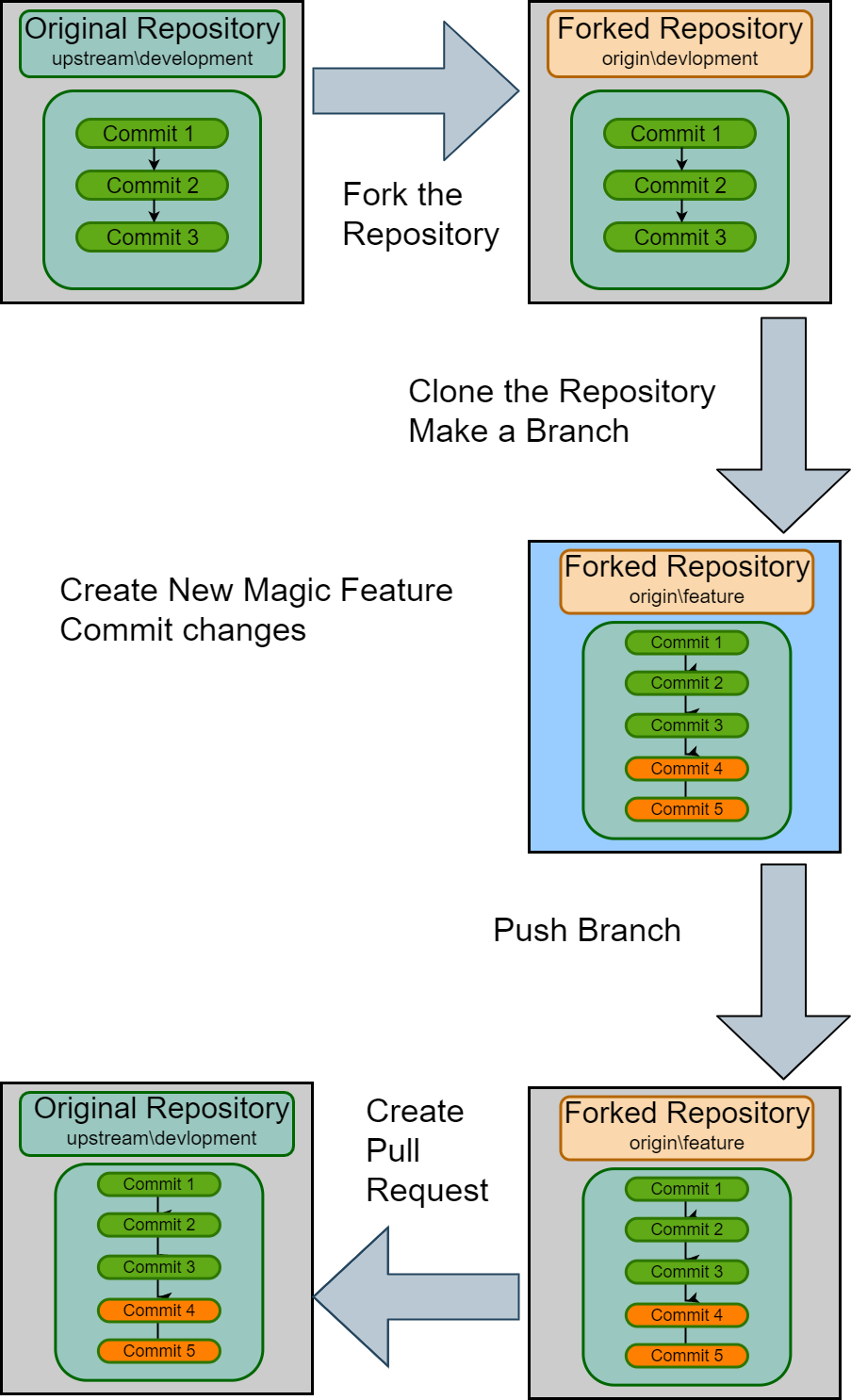

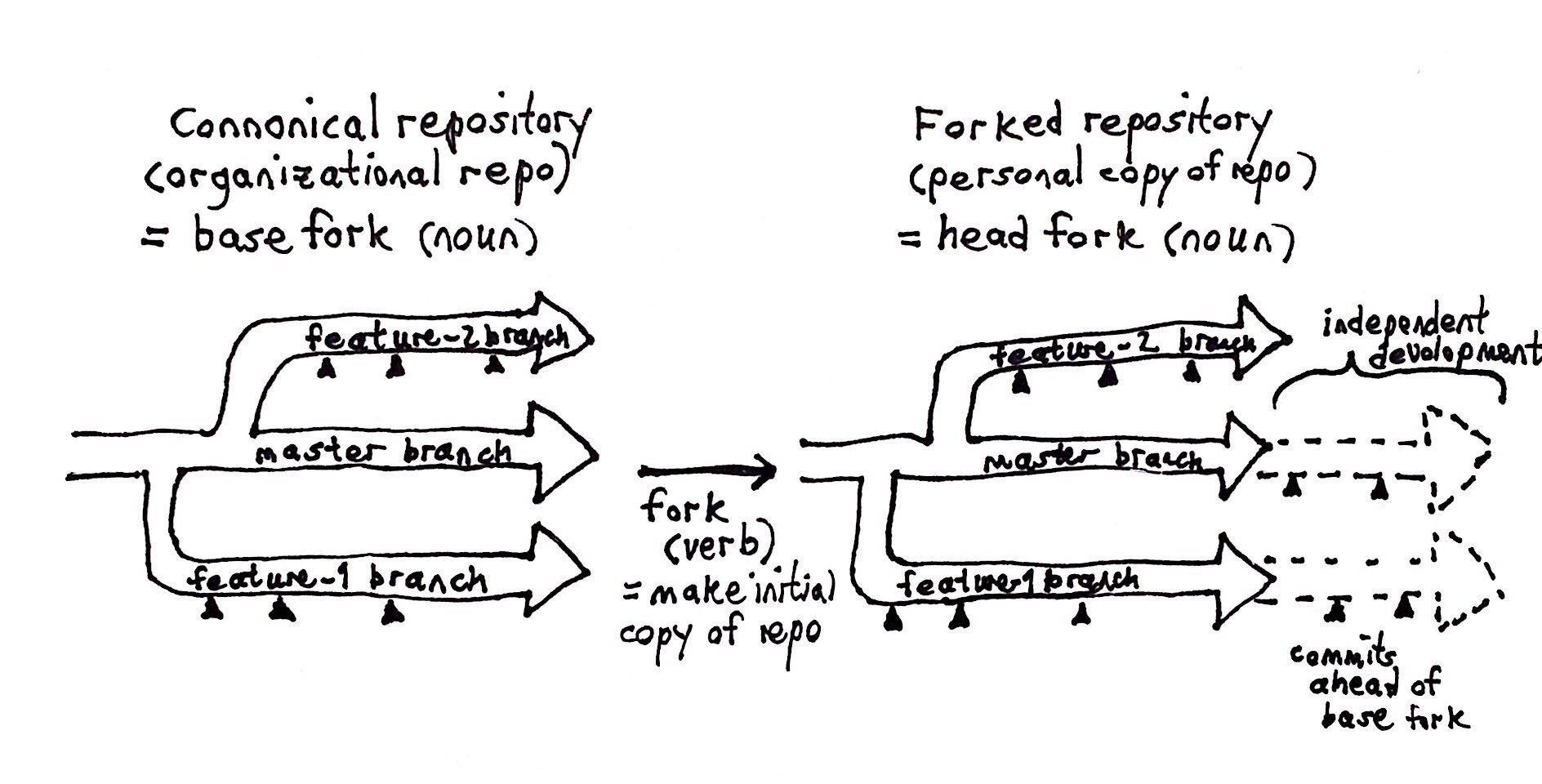

Forking a repository creates a personal or organizational copy of another user’s project on GitHub. This forked repository inherits the code and visibility settings of the original (often called the “upstream”) repository but is otherwise independent—changes made in the fork do not affect the original, unless those changes are explicitly merged via a pull request[^1jsxhq][^1qb0if][^jb59ow].

A practical example is seen in open source software communities. Suppose a developer wants to propose a bug fix to a widely-used project. Rather than requesting write access or working directly in the main repository, they simply fork it, make the corrections in their own copy, and then submit a pull request. This initiates a review process, allowing maintainers to decide whether to merge the changes into the main project[^60ymhq][^1qb0if][^jb59ow].

Forking also supports divergent experimentation. A user may fork a project to try out a new feature or architectural change, or to tailor software for a unique use case. If these changes prove valuable, they can be proposed to the upstream maintainers; if not, the fork can remain as a fully functional independent project[^1qb0if][^jb59ow].

Other common uses for forks include educational projects, quick prototyping, and internal adaptations of open source code. For example, organizations may fork an open source library to customize it for their infrastructure while still benefiting from upstream updates[^jb59ow].

Benefits and Applications

- Isolation for Safe Experimentation: Users can test ideas or develop features without risking the stability of the main codebase[^1jsxhq][^1qb0if].

- Democratized Contribution: Anyone can participate; contributions are merged only after review, supporting secure collaboration in large, decentralized teams[^60ymhq].

- Open Innovation: Forked repositories enable communities to rapidly innovate and iterate, benefiting widely-used frameworks and libraries[^60ymhq][^jb59ow].

Challenges and Considerations

Despite its strengths, forking also introduces potential challenges:

- Synchronization: Keeping forked repositories updated with frequent upstream changes can be complex.

- Fragmentation: Excessive or unmanaged forking may lead to fragmentation, where improvements are siloed and not merged upstream, diluting collective progress.

- Ownership and Privacy: For private repositories, if the root repository is deleted, its forks are also removed; for public projects, the fork owner controls the fork even if the original disappears[^1jsxhq][^1qb0if].

Current State and Trends

Forking is now a standard part of GitHub workflows, especially in open source. Major open-source organizations and countless individual developers use forking to contribute without needing approval for direct write access[^60ymhq][^1qb0if]. This model is not limited to GitHub; other platforms, like GitLab and Bitbucket, also use similar forking workflows.

Key players like the Linux Foundation, Apache Software Foundation, and large corporate tech contributors (Microsoft, Google, Facebook) rely on fork-based collaboration to manage contributions across vast and distributed communities. GitHub’s interface has streamlined forking, enabling users at any experience level to participate[^60ymhq].

Recent developments include improved pull request handling, automation for keeping forks updated with upstream changes, and enhanced filtering and discovery tools to manage the massive ecosystem of forks within large projects[^1qb0if].

Future Outlook

As collaboration tools evolve, forked repositories will be further integrated with automation and AI-driven features, streamlining code reviews and synchronizations. The next wave of enhancements may include automated conflict resolution, real-time fork synchronization, and more granular permission models—making large-scale, open collaboration even more efficient. This will lower the barrier to entry and broaden the diversity and volume of contributions to important open source and private projects.

[IMAGE 3: Forked/Forking Repositories on GitHub future trends or technology visualization]

Forked repositories on GitHub have transformed project collaboration, enabling vibrant, global innovation. As these tools evolve, expect forking workflows to become ever more central to software development’s future.

Sources

[^1jsxhq] https://github.com/orgs/community/discussions/35849

[^60ymhq] https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/comparing-workflows/forking-workflow

[^1qb0if] https://docs.github.com/en/pull-requests/collaborating-with-pull-requests/working-with-forks/about-forks

[^jb59ow] https://heardlibrary.github.io/digital-scholarship/manage/control/github/fork/

[^cd22y0] https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=20001570